This day in history – “Teapot Dome” became synonymous with outrage, political scandal and a disgraceful event.

You remember history, that thing we’re destined to repeat if we don’t remember it?

What happened, you ask?

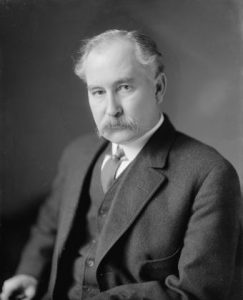

In 1920, Warren G. Harding, a senator and Ohio newspaper publisher, won a long-shot bid for the White House with the financial backing of oilmen who were promised oil-friendly cabinet picks in return.

In 1920, Warren G. Harding, a senator and Ohio newspaper publisher, won a long-shot bid for the White House with the financial backing of oilmen who were promised oil-friendly cabinet picks in return.

Harding’s campaign slogan for the election was “Return to normalcy,” a return to the way of life before World War I. His promise was to return the United States to its prewar greatness after the hardships of World War I (1914-1918). (Hmm, Make America Great?) As president, Harding favored pro-business policies, diminished conservation, and limited immigration.

Even though it lasted only from 1921 to 1923 (Harding died in 1923), Harding’s administration became the most scandal-ridden to date, thanks to his political friends. Attorney General Harry Daugherty was accused of profiting from the sale of government alcohol supplies during Prohibition, as well as selling pardons. Harding’s head of the Veterans Bureau, Charles Forbes, was sentenced to two years in prison for bribery and corruption. Other scandals involved appointees in the Shipping Bureau and Alien Property Custodians office. And, Harding’s Secretary of the Interior, Albert B. Fall, announced his resignation in the midst of an unfolding scandal that would become known as Teapot Dome.

Now I’d heard of the Teapot Dome scandal, but didn’t really know what was involved, so on a whim, I did a little research. (It’s what authors do, usually when they’re procrastinating.)

The Teapot Dome Scandal of the 1920s shocked Americans by revealing an unprecedented level of greed and corruption within the federal government. The scandal involved ornery oil tycoons, poker-playing politicians, illegal liquor sales, a murder-suicide, a womanizing president and a bagful of bribery cash.

During the Teapot Dome scandal, Albert B. Fall was found guilty of accepting a bribe while in office. (Fall claimed it was a loan from Doheny worth about $5 million in today’s dollars. He was unable to justify the ~$15 million in cash and bonds he received from Sinclair. Some sources say it was “only” $10 million.) Fall was the first individual to be convicted of a crime committed while a presidential cabinet member.

During the Teapot Dome scandal, Albert B. Fall was found guilty of accepting a bribe while in office. (Fall claimed it was a loan from Doheny worth about $5 million in today’s dollars. He was unable to justify the ~$15 million in cash and bonds he received from Sinclair. Some sources say it was “only” $10 million.) Fall was the first individual to be convicted of a crime committed while a presidential cabinet member.

Fall attempted to transfer control of the Forest Service from the Department of Agriculture. He wanted the natural resources of the Alaska Territory (apparently for his own use), but was no match for the Agriculture Secretary–and future Vice President–Henry Wallace. He was more “successful” with the US Naval oil-reserves. As the Navy converted from coal-powered to oil-fueled ships, the reserves insured there was sufficient oil in the event of another war.

Fall convinced Warren G. Harding to transfer supervision of the land from the Navy to the Department of the Interior in May 1921 (which Harding did by Executive Order). Fall then secretly granted exclusive rights to the Teapot Dome(Wyoming) reserves to Harry F. Sinclair of the Mammoth Oil Company (April 7, 1922). (He also made similar rights grants to Edward L. Doheny of Pan American Petroleum Company for the Elk Hills and Buena Vista Hills reserves in California (1921–22).)

What brought Fall down was a Congress that actually investigated instead of staging political shows and a Justice Department that “followed the money.” Fall’s personal financial position improved dramatically following the lease grants, attracting the attention of Senate investigators. Special prosecutors were appointed and the investigation unraveled the crime.

In 1929, Fall became the first former Cabinet officer ever convicted of a felony committed while in office. He was fined $100,000, which he never paid, and served only nine months of a one-year prison sentence. “My version of the matter is simply that I was not guilty,” he told the parole board. (Ironically enough, after resigning, Fall took part in lucrative oil deals in Russia and Mexico with both Doheny and Sinclair.)

Doherty was never charged, but Sinclair refused to answer some of the Senate team’s questions, claiming that Congress had no right to probe his private affairs. That refusal was challenged and eventually reached the Supreme Court. In the 1929, Sinclair vs. United States ruling, the court said that Congress did have the power to fully investigate cases where the country’s laws may have been violated. Sinclair would later serve six months in prison for contempt of Congress and jury tampering.